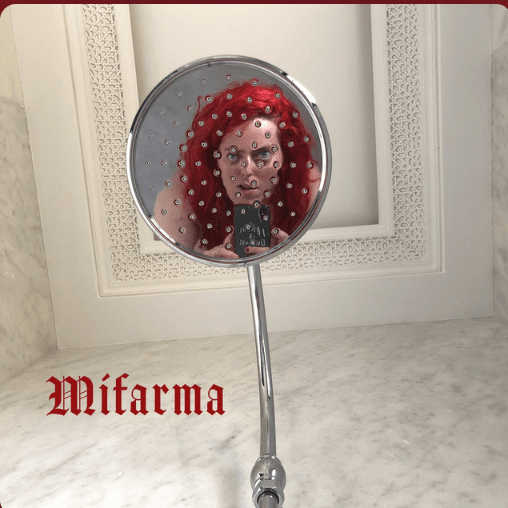

There’s a particular kind of album that arrives not with fanfare but with a whisper, demanding you lean in closer to catch what it’s trying to say. Danielle Alma Ravitzki’s debut as Mifarma is precisely that—a collection that refuses the conventional narrative arc of suffering-struggle-redemption that dominates so much contemporary music about personal hardship.

What Ravitzki has crafted instead is something far more uncomfortable and, ultimately, more honest: a document of stasis, of being stuck in the process, of the maddening reality that healing doesn’t follow a linear path with clear milestones. Across eight tracks, she dismantles the expectation that art about trauma must either provide therapeutic release or offer inspirational transformation. Mifarma does neither, and that’s precisely its power.

The Sound of Processing

Carmen Rizzo’s production choices establish the album’s aesthetic language immediately. Rather than burying vocals in reverb or drowning emotion in maximalist arrangements, Rizzo opts for unsettling clarity. Every breath, every hesitation in Ravitzki’s delivery is audible. It’s an exposed nerve of a mix, one that makes the listener complicit in the intimacy being shared.

The instrumentation operates on principles of subtraction rather than addition. Where many electronic-leaning records pile on synths and beats to build momentum, Mifarma strips away. A piano line enters, plays its part, and vanishes before wearing out its welcome. Percussion, when it appears, feels more like a heartbeat monitor than a rhythm section—present to confirm life, not to energize it.

This minimalism serves the material brilliantly. These songs aren’t about energy or movement; they’re about being trapped in your own head, about the exhausting work of simply existing when your internal landscape has become hostile territory. The sparse arrangements mirror that psychological claustrophobia without resorting to obvious sonic signifiers of distress.

Ravitzki as Narrator

The central figure in this musical ecosystem is Ravitzki herself, whose vocal approach defies easy categorization. She’s not a belter, not a whisperer, not a technical acrobat. Instead, she sings with the cadence of someone speaking difficult truths to a therapist—measured, careful, occasionally breaking but never collapsing entirely.

There’s a particular moment in the album’s midsection where her voice cracks slightly on a sustained note, and rather than re-recording for a cleaner take, the imperfection remains. It’s a small choice that encapsulates the entire project’s ethos: perfection would be a lie. These songs demand authenticity over polish, documentation over performance.

Her lyrical sensibility leans toward the observational rather than the confessional. She describes states of being without editorializing them, presenting psychological experiences as simple facts rather than events requiring interpretation. “I did this,” “I felt that,” “this happened”—the accumulation of these declarative statements builds a portrait of someone watching themselves from a distance, neither condemning nor forgiving what they see.

The Architecture of Avoidance

What makes Mifarma genuinely distinctive is its structural resistance to resolution. Traditional songwriting builds tension and releases it; verses set up choruses that provide emotional payoff. Mifarma systematically subverts these expectations. Songs end not at natural conclusions but at arbitrary stopping points, as if Ravitzki simply ran out of things to say on that particular subject and moved on.

This creates a listening experience that can feel deliberately frustrating. You keep waiting for the moment where everything breaks open, where the carefully maintained composure shatters and raw emotion floods through. It never comes. The album maintains its temperature throughout, neither heating up nor cooling down, existing in a perpetual emotional twilight.

Some will find this monotonous. And in weaker moments, that criticism holds water—a few tracks do blur together, victims of their own commitment to sameness. But viewed as a complete statement, this uniformity serves a purpose. Living with unresolved trauma isn’t dynamic or varied; it’s repetitive, grinding, relentless in its sameness. The album replicates that experience without romanticizing it.

Collaborators as Co-Conspirators

The assembled cast of contributors—Shara Nova, Earl Harvin, Melissa Lingo, Piers Faccini—operate more as enablers of Ravitzki’s vision than as guests making cameos. Their fingerprints are present but subtle, enhancing textures without dominating them. Nova’s influence particularly seems to inform the album’s willingness to embrace dissonance and asymmetry, to let songs exist in states of irresolution.

The fact that women composed nearly every track creates an unspoken solidarity throughout the record. This isn’t explicitly political music, but the shared perspective creates a kind of implicit understanding, a recognition that certain experiences don’t require extensive explanation because the listener already knows. It’s community-building through artistic practice rather than through lyrical proclamation.

The Bigger Picture

Mifarma arrives at a cultural moment saturated with trauma narratives, where everyone’s processing their damage publicly, where vulnerability has become its own kind of performance. Against this backdrop, Ravitzki’s refusal to make her pain consumable or her recovery inspirational feels almost radical.

This is emphatically not music designed to make you feel better. It won’t pump you up for your morning run or provide a satisfying cry during your commute. What it offers instead is recognition—the sense that someone else understands how maddeningly slow and non-linear the work of rebuilding yourself actually is, how little the process resembles the redemption arcs we’re sold in movies and memoirs.

There’s a kind of generosity in that honesty, even if it doesn’t feel generous in the moment. Ravitzki isn’t here to coach you through your difficulties or assure you everything will be fine. She’s simply documenting her own experience with unflinching clarity and trusting that the documentation itself has value, that bearing witness counts for something.

Final Verdict

Mifarma’s debut won’t be for everyone, and it doesn’t aspire to be. This is challenging, occasionally frustrating, determinedly unhurried music that asks for patience and attention in an era that rewards neither. But for listeners willing to meet it on its own terms, it offers something increasingly rare: an honest account of what living through difficulty actually feels like, stripped of narrative convenience and emotional manipulation.

Ravitzki has announced herself as an artist of considerable vision and discipline, someone willing to sacrifice accessibility in service of authenticity. Whether she’ll maintain this uncompromising approach or evolve toward more varied terrain remains to be seen. For now, Mifarma stands as a stark, occasionally beautiful, deeply uncomfortable meditation on the parts of healing no one wants to talk about—the boring parts, the repetitive parts, the parts where nothing seems to be happening at all but somehow the work continues anyway.