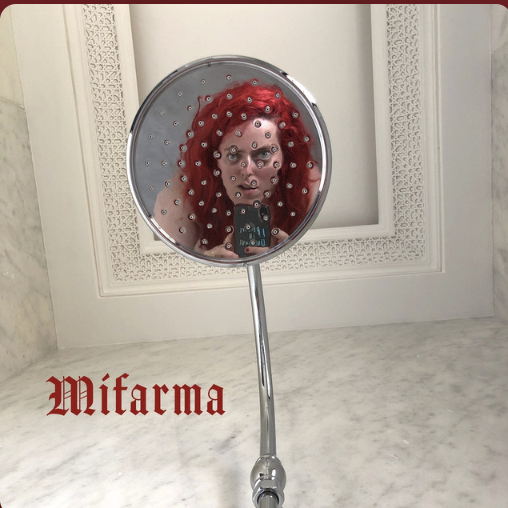

Mifarma doesn’t arrive as a project so much as an atmosphere. Born from the intensely personal experiences of Danielle Ravitzki, the moniker became a vessel for songs that live in shadow and stillness, where vulnerability is delivered in near-whispers and emotional clarity feels devastatingly precise. Across this body of work, she embraces minimalism, space, and a deliberate slowness that allows each sound to breathe, creating music that exists somewhere between dream and confession. In this interview, Mifarma speaks about the first song that opened the emotional landscape of the album, the choice to separate this material from her own name, the quiet rituals that shaped her time in the studio, and the deep transformation that led to an album that resists categorization and insists on honesty above all else.

What was the first song you wrote for this album, and did it set the template for everything that followed or did the project evolve away from that initial direction?

The first song I wrote for the album was Somnambulist. It didn’t set a template as much as it revealed a landscape. The song lives in that quiet, suspended space after the event, when the body is still moving, but the soul is catching up. Once I found that emotional vocabulary, everything else grew around it. The project kept evolving, but that atmosphere of restrained intensity, of saying something devastating almost under a whisper, became the gravitational center. Even when later songs took different shapes, they always circled back to that same internal darkness and clarity.

You chose to release this under the name Mifarma rather than your own. What does that moniker mean to you, and why did this material need its own identity?

Releasing the album under the name Mifarma created a necessary barrier between me and the songs. The material is extremely personal, and having that slight distance allowed me to express myself more honestly. The moniker became a kind of vessel, something that could hold the intensity of the stories without overwhelming me as Danielle. It let me go deeper, darker, and more vulnerable than I could have under my own name.

How long did you live with these songs before you felt ready to record them? Was there a moment when you knew they were done or could you have kept working indefinitely?

Some of these songs lived with me for years before I felt ready to record them. They changed with me as I changed. There wasn’t a single moment where I suddenly knew they were ‘done’, it was more like accepting that they had reached the point where they could stand on their own. I could have kept shaping them forever, but recording them meant letting them go, trusting that they said what they needed to say in that moment. Also, I am not the type of artist that can just write for myself, and keep the songs in my drawer. Releasing and sharing the poems or the music is a big part of what makes this therapeutic.

The production feels like it’s breathing, with lots of room for individual sounds to exist. Were there disagreements with Carmen about how much space to leave or were you aligned from the beginning?

We were mostly aligned, but there were moments where I wanted more space and Carmen pushed for a little more texture, or the other way around. But those tensions were always creative. They helped us figure out exactly how much air the songs needed. In the end, we met in a place where the production feels alive, not overloaded.

Can you walk us through a typical day in the studio? What time did you work best, and were there rituals or routines that helped you access the emotional headspace these songs required?

Because the songs came from very personal experiences, I couldn’t force myself into the emotional space they required. We usually worked later in the day, after everything else had quieted down. My only ritual was to sit alone for a few minutes and check in with myself, am I able to go there today? Can I revisit this memory without shutting down? That small pause helped me stay grounded. Carmen and I worked slowly, with a lot of intention, so nothing felt rushed or performative.

Which track on the album was the hardest to finish and why? Were there any that almost didn’t make it?

I don’t actually feel like any of the tracks were hard to finish. By the time I went into the studio, I was in a very grounded and healthy emotional place, so I was able to move through each song with clarity. The only thing that didn’t make it onto the album was a song composed by Melissa Lingo (she also composed ‘Rejection Is My Pendant.’) It’s a beautiful piece, but it belongs to the emotional landscape of the next record, so I’m saving it for that.

You’ve created something that resists easy categorization. When people ask what kind of music you make, how do you describe it without underselling what makes it unique?

I usually tell people it’s alternative music that blends minimalism, folk influences, and experimental production, but the emotional world matters more than the genre. It lives somewhere between dream and confession. It’s intimate, sparse, and a little unsettling in places. I don’t try to squeeze it into a label; I just describe the atmosphere it creates.

Did writing and recording this album change you, or was it more about documenting a change that had already happened?

The transformation came first; the album was the archive of that transformation. But in turning my experiences into music, something else shifted: I recognized the person I had become. The album didn’t initiate the change, but it made it audible, which is its own kind of becoming.

Are there artists or albums that influenced the sonic direction here, even if they don’t sound anything like what you ended up creating?

There were definitely artists who influenced my approach, even if the final sound doesn’t resemble theirs at all. I was inspired by people who understand space, artists like Sufjan Stevens, Bjork, and Shara Nova, musicians who let silence carry as much emotional weight as sound. Those influences were more about philosophy than imitation. They helped me trust the minimalism and the breathing quality of the production.

The album avoids anything that feels manipulative or designed to provoke specific emotional responses. How do you test whether a moment is genuine versus performative when you’re in the middle of creating it?

I can sense when something turns performative because it feels like I’m stepping outside myself and watching instead of inhabiting the moment. So I always return to stillness. If the line or sound sits comfortably in silence if it breathes on its own, then it’s genuine. If it clamors for attention, it isn’t. The album’s truth came from resisting the urge to dramatize what was already dramatic on its own.

What do you hope happens when someone listens to this alone at night? Is there an ideal context or state of mind for experiencing these songs?

I hope the listener feels a sense of permission. The permission to sit with whatever is happening inside them without trying to fix it. These songs were meant to be experienced in quiet, when you can hear your own breath. There’s no ideal emotion, just openness. If someone listens alone at night, I hope the music feels like a companion rather than a demand.

Looking back at the process now, is there anything you wish you’d done differently, or does the album feel like exactly what it needed to be?

I see the album as a record of who I was then, not who I am now. And because of that, I don’t wish it were different. Any change would distort the honesty of that moment. It needed to sound exactly like the version of me who made it, no more and no less.